Experts' Scenarios on Russia's Future

By Dr. S. Frederick Starr, ed.

January 18, 2024

Experts' Scenarios on Russia's Future

What does Russia’s future hold? Of course, we don’t know. For a century determinists of various persuasions claimed to be able to predict future developments. They believed that a very few key economic or social indicators determined humankind’s future evolution. Nowadays all but the most diehard determinists accept that a broad range of factors contribute to the direction of change. We acknowledge that along with economic and social change, factors as diverse as the values and personalities of leaders, the dynamics of groups and bureaucracies, changing sources of energy, group and national psychology, and even changes in climate can all shape the future.

What does Russia’s future hold? Of course, we don’t know. For a century determinists of various persuasions claimed to be able to predict future developments. They believed that a very few key economic or social indicators determined humankind’s future evolution. Nowadays all but the most diehard determinists accept that a broad range of factors contribute to the direction of change. We acknowledge that along with economic and social change, factors as diverse as the values and personalities of leaders, the dynamics of groups and bureaucracies, changing sources of energy, group and national psychology, and even changes in climate can all shape the future.

These and many other factors could affect the outcome of Russia’s current war on the Ukraine and developments within the Russian Republic immediately thereafter.

consensus? And if there is consensus in any area, does it acknowledge the possible importance of what Donald Rumsfeld called the “unknown unknowns”?

decade. We made a point of asking for their views on what will happen,

and not what they believe should happen. This paper presents the

thoughts of 25 respondents from 16 countries. Of course, the list could

Experts’ Scenarios on Russia’s Futures have been extended indefinitely to assure that all of the main perspectives would be represented. But ars longa, vita brevis. We are deeply grateful to

those who found time to contribute to this compendium and acknowledge

the good intentions of the many others who were not able to do so.

questions about Russia’s immediate future. Others may reject them all,

while yet others—and these are our target audience—may be so inspired

or infuriated by what they find in this collection as to lead them to pen

their own prognostications

Click here to read the full article (PDF)

S. Frederick Starr, Ph.D., is the founding chairman of the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center, and a Distinguished Fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.

ASIA Spotlight with Prof. S. Frederick Starr on Unveiling Central Asia's Hidden Legacy

On December 19th, 2023, at 7:30 PM IST, ASIA Spotlight Session has invited the renowned Prof. S Fredrick Starr, who elaborated on his acclaimed book, "The Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane." Moderated by Prof. Amogh Rai, Research Director at ASIA, the discussion unveiled the fascinating, yet lesser-known narrative of Central Asia's medieval enlightenment.

The book sheds light on the remarkable minds from the Persianate and Turkic peoples, spanning from Kazakhstan to Xinjiang, China. "Lost Enlightenment" narrates how, between 800 and 1200, Central Asia pioneered global trade, economic development, urban sophistication, artistic refinement, and, most importantly, knowledge advancement across various fields. Explore the captivating journey that built a bridge to the modern world.

To know watch the full conversation: #centralasia #goldenage #arabconquest #tamerlane #medievalenlightment #turkish #economicdevelopment #globaltrade

Click here to watch on YouTube or scroll down to watch the full panel discussion.

Some Lessons for Putin from Ancient Rome

ABOUT THE AUTHORS: S. Frederick Starr, is a distinguished fellow specializing in Central Asia and the Caucasus at the American Foreign Policy Council and founding chairman of the Central Asia Caucasus Institute.

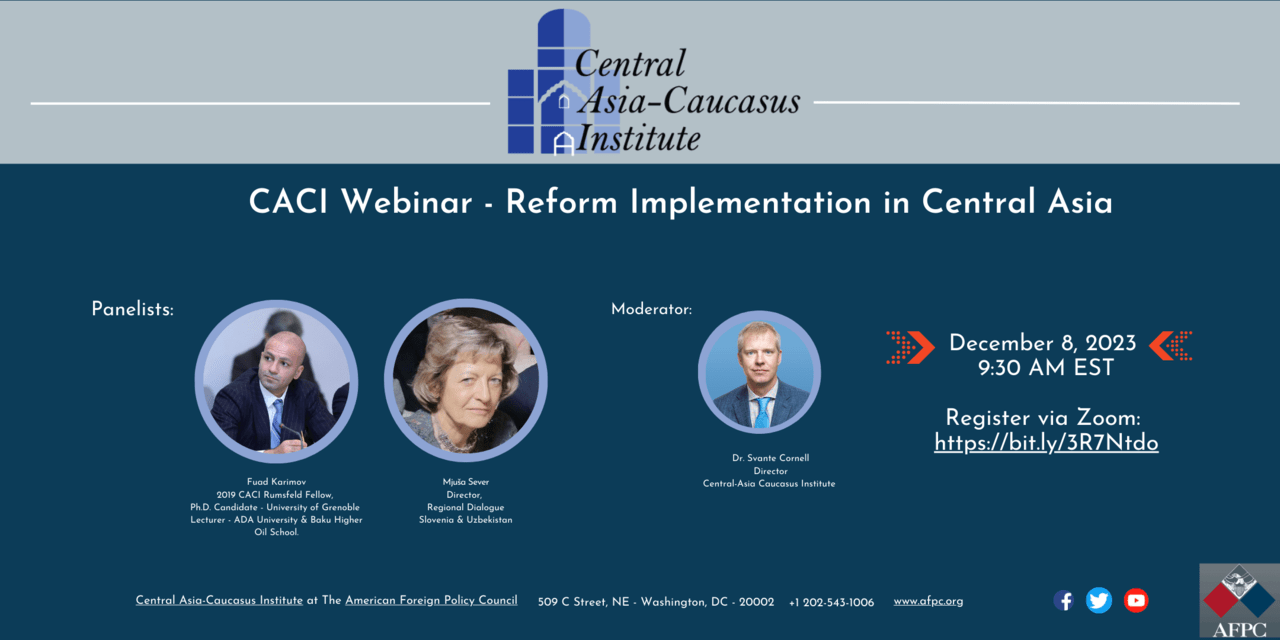

Watch the 12/8 CACI Webinar - Reform Implementation In Central Asia

Central Asian governments, particularly Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, have embarked on a series of reform initiatives in recent years. Announcing far-reaching reforms is one thing, but implementation is another. This CACI webinar delves into the question how the process of implementation of reform agendas is processing.

PANELISTS:

- Mjusa Sever, Director, Regional Dialogue, Slovenia & Uzbekistan

- Fuad Karimov, 2019 CACI Rumsfeld Fellow, Ph.D. Candidate - University of Grenoble and Lecturer - ADA University & Baku Higher Oil School

MODERATER:

- Dr. Svante Cornell, Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute

Watch the video below or on YouTube

Watch the 12/4 CACI Webinar - Is the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor Happening?

The vision of a transportation corridor linking Europe to Asia through the Caucasus and Central Asia was conceived almost a soon as the USSR collapsed. However, in spite of progress, major infrastructure remains to be built for this corridor to truly matter. In the past year, geopolitical developments have spurred the states in Central Asia and the Caucasus into action. Major regional states have linked arms like never before to speed this corridor into realization. To discuss the corridor, its challenges and its implications, the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute invites you to the following web-based Forum.

PANELISTS:

- Gen. Gaidar Abdikerimov, Secretary General, TITR (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route)

- Dr. Charles Kunaka, Lead Transport Specialist, Transport Global Practice, World Bank

- Dr. Brenda Shaffer, Research Faculty Member, Energy Academic Group, Naval Postgraduate School

- Dr. Mamuka Tsereteli, Senior Fellow, CACI

MODERATOR:

- Dr. Svante Cornell, Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute