U.S. & Greece: Cementing a Closer Strategic Partnership

U.S. & Greece: Cementing A Closer Strategic Partnership

JINSA

January 30, 2020

JINSA Eastern Mediterranean Task Force

Dormant for decades, the Eastern Mediterranean is back as a cockpit of competition, and concerted U.S. reengagement with the region is increasingly necessary. This imperative is most evident when it comes to America’s relations with Greece.

More and more, Athens is becoming a crucial, pro-U.S. geopolitical actor at the center of every key regional security issue. The primary driver of regional change has been Turkey’s transformation under President Erdoğan from a democratic and reliable NATO partner to a pro-Russian autocracy hostile to the West. A major potential flashpoint between Turkey and its neighbors Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt comes from the simultaneous discovery of considerable natural gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean.

These major regional developments have helped drive a fundamental reorientation of Greece’s foreign policy. There is growing national consensus in Athens that a strong relationship with the United States should form the bedrock of Greece’s security. Greece aspires to take over Ankara’s role as the southeastern bastion of the Western alliance, and to become a diplomatic and economic hub interlinking Europe and other growing regional players like Israel, Cyprus and Egypt.

Yet, Greece needs deeper U.S. cooperation if it is to become a platform for projecting American power and promoting regional stability. Our policy project has developed a comprehensive set of recommendations for U.S. policymakers to bolster this expanding bilateral relationship.

The United States should go beyond rhetorical support for Greece’s and Cyprus’ trilateral diplomatic fora with Israel and Egypt. Washington should also strengthen Greece’s ability to defend U.S. interests by increasing bilateral military-to-military ties, including by providing meaningful amounts of foreign military financing (FMF) for Greece to purchase U.S. weapons and materiel. Depending on the trajectory of relations with Turkey, American policymakers should also consider how they might strengthen the U.S. security relationship with Cyprus, which until December 2019 was largely blocked by a U.S. arms embargo. Consideration of additional steps would have to be undertaken in conjunction with an assessment of broader U.S. efforts to resolve the Cyprus issue as a whole. The United States should explore options to bolster its own forward military presence in Greece, and should view Greece and potentially Cyprus as viable, and reliable, options for relocating U.S. military assets currently deployed in Turkey. With Greece indicating its willingness to host most or all these forces, American policymakers should explore relocating some forces to Greece and develop options for further relocations in the event that their continued presence in Turkey becomes unsustainable.

Click here to read the report.

Eastern Mediterranean Policy Project Co-Chairs

Amb. Eric Edelman

Former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy

Gen Charles “Chuck” Wald, USAF (ret.)

Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command

Eastern Mediterranean Policy Project Members

Gen Philip M. Breedlove, USAF (ret.)

Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander and former Commander of U.S. European Command

Gen Kevin P. Chilton, USAF (ret.)

Former Commander, U.S. Strategic Command

Svante E. Cornell

Policy Advisor, JINSA Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy

ADM Kirkland H. Donald, USN (ret.)

Former Director, Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program

VADM Mark Fox, USN (ret.)

Former Deputy Commander, U.S. Central Command

ADM Bill Gortney, USN (ret.)

Former Commander, North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD)

John Hannah

Former Assistant for National Security Affairs to the Vice President; JINSA Gemunder Center Senior Advisor

Reuben Jeffery

Former Under Secretary of State for Economic, Business and Agricultural Affairs

Alan Makovsky

Former Senior Professional Staff Member at U.S. House Foreign Relations Committee

GEN David Rodriguez, USA (ret.)

Former Commander, U.S. Africa Command

Lt Gen Thomas “Tom” Trask, USAF (ret.)

Former Vice Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command

Occupied Elsewhere: Selective Policies on Occupations

Foundation for Defense of Democracies

January 27, 2020

Svante E. Cornell and Brenda Shaffer

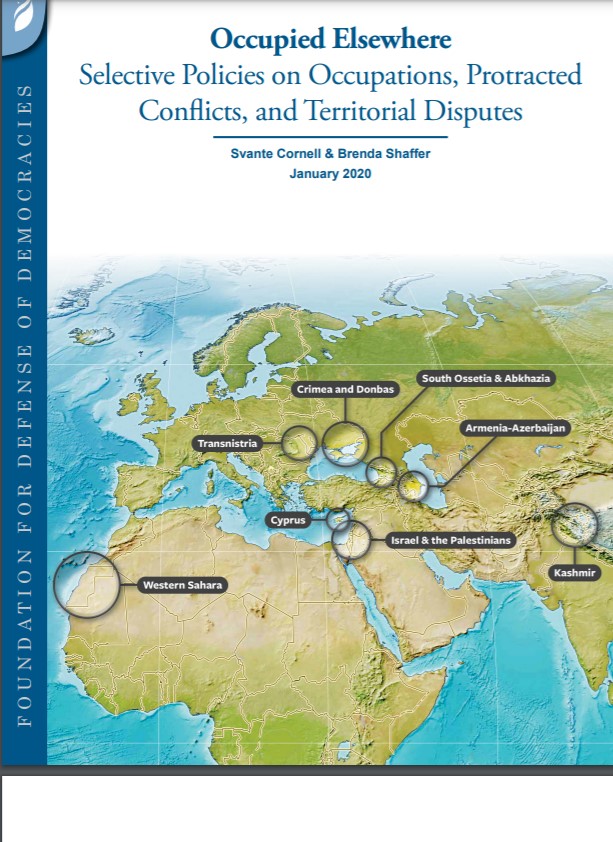

Setting policies toward territories involved in protracted conflicts poses an ongoing challenge for governments, companies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Since there are multiple zones of disputed territories and occupation around the globe, setting policy toward one conflict raises the question of whether similar policies will be enacted toward others. Where different policies are implemented, the question arises: On what principle or toward what goal are the differences based?

Setting policies toward territories involved in protracted conflicts poses an ongoing challenge for governments, companies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Since there are multiple zones of disputed territories and occupation around the globe, setting policy toward one conflict raises the question of whether similar policies will be enacted toward others. Where different policies are implemented, the question arises: On what principle or toward what goal are the differences based?

Recently, for example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) decided goods entering the European Union that are produced in Jewish settlements in the West Bank must be clearly designated as such. At the same time, however, neither the ECJ nor the European Union have enacted similar policies on goods from other zones of occupation, such as Nagorno-Karabakh or Abkhazia. The U.S. administration swiftly criticized the ECJ decision as discriminatory since it only applies to Israel. Yet, at the same time, U.S. customs policy on goods imports from other territories is also inconsistent: U.S. Customs and Border Protection has explicit guidelines that goods imported from the West Bank must be labelled as such, while goods that enter the United States from other occupied zones, such as Nagorno-Karabakh, encounter no customs interference.

Territorial conflicts have existed throughout history. But the establishment of the United Nations, whose core principles include the inviolability of borders and the inadmissibility of the use of force to change them, led to the proliferation of protracted conflicts. Previously, sustained control over territory led to eventual acceptance of the prevailing power’s claims to sovereignty. Today, the United Nations prevents recognition of such claims but remains largely incapable of influencing the status quo, leaving territories in an enduring twilight zone. Such territories include, but are not limited to: Crimea, Donbas, Northern Cyprus, the West Bank, Kashmir, The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Transnistria, and Western Sahara.

The problem is not simply that the United Nations, United States, European Union, private corporations, and NGOs act in a highly inconsistent manner. It is that their policies are selective and often reveal biases that underscore deeper problems in the international system. For example, Russia occupies territories the United States and European Union recognize as parts of Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, yet Crimea is the only Russian-occupied territory subject to Western sanctions. By contrast, products from Russian-controlled Transnistria enter the United States as products of Moldova, and the European Union allows Transnistria to enjoy the benefits of a trade agreement with Moldova. The United States and European Union demand specific labeling of goods produced in Jewish settlements in the West Bank and prohibit them from being labeled Israeli products. Yet products from Nagorno-Karabakh – which the United States and European Union recognize as part of Azerbaijan – freely enter Western markets labeled as products of Armenia.

Today, several occupying powers try to mask their control by setting up proxy regimes, such as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) or similar entities in Transnistria and Nagorno-Karabakh. While these proxies do not secure international recognition, the fiction of their autonomy benefits the occupier. By contrast, countries that acknowledge their direct role in a territorial dispute tend to face greater external pressure than those that exercise control by proxy.

Some territorial disputes have prompted the forced expulsion or wartime flight of the pre-conflict population. A related issue is the extent to which the occupier has allowed or encouraged its own citizens to become settlers. While one might expect the international system to hold less favorable policies toward occupiers that drive out residents and build settlements, this is not the case. Armenia expelled the Azerbaijani population of Nagorno-Karabakh, yet the United States and European Union have been very lenient toward Armenia. They have also been lenient toward Morocco, which built a 1,700-mile long barrier to protect settled areas of Western Sahara and imported hundreds of thousands of settlers there. Against this backdrop, the constant pressure to limit Israeli settlement in the West Bank is the exception, not the rule.

This pressure is even more difficult to grasp given that Israel’s settlement projects in the West Bank consist of newly built houses. In most other conflict zones, such as Northern Cyprus and Nagorno-Karabakh, settlers gained access to the homes of former residents.

This study aims to provide decision makers in government as well as in the private sector with the means to recognize double standards. Such standards not only create confusion and reveal biases, but also constitute a business and legal risk. New guidelines for making consistent policy choices are therefore sorely needed.

CACI Forum with recording: An Increasingly Polarized Georgia: What Should America Do?

An Increasingly Polarized Georgia: What Should America Do?

Georgia has entered an election year with an extremely polarized political environment. In 2019, the ruling Georgian Dream party promised and advertised a move to a proportional electoral system with a zero threshold for parliamentary representation. Its reversal of this decision in November caused significant political turmoil, and led a significant pro-Western fraction to leave the ruling party. The otherwise fractured opposition is now consolidated in its demand for electoral reforms, putting the legitimacy of the election process in question. At several earlier times, the U.S. has taken a role to assist Georgia in difficult times like this. Could it do so again? Should it?

Speakers:

Michael Carpenter, Managing Director, Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement

Ambassador Richard Miles, Former US Ambassador to Georgia

Anthony C. Bowyer, Europe & Eurasia Advisor, International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES)

Moderator: Svante Cornell, Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at AFPC

Where: American Foreign Policy Council: 509 C Street NE, Washington, DC 20002

When: Tuesday, February 18, 2020 from 2:00 - 3:45 pm

Scroll down to watch the event.

CACI Forum Invitation: Are We Getting Closer to Peace in Afghanistan?

Are We Getting Closer to Peace in Afghanistan?

In the claustrophobic atmosphere of Kabul today, uncertainty reigns on every side: security, politics, business, and finance. Afghanistan is a big country, and Afghan society is rapidly changing. Are there compensating factors that we are ignoring and, if so, what are they?

Speaker: Mr. Shoaib Rahim, Senior Adviser, Afghanistan's State Ministry for Peace

Moderator: S. Frederick Starr, Chairman, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at AFPC

Where: American Foreign Policy Council: 509 C Street NE, Washington, DC 20002

When: Tuesday, January 21, 2020 from 2:00 - 4:00 pm,

RSVP: Click HERE to register

America Must Defend Its Allies Against Clear Russian Hostility

Mamuka Tsereteli

The Hill, December 10, 2019

It is in American interests to deter an increasingly assertive Russia. One way of doing this is to strengthen the independence and sovereignty of the countries around Russia, most of which face growing pressure from Moscow. The Black Sea states of Ukraine and Georgia, as well as Moldova and Belarus, are primary targets of Russian power. Other countries of the South Caucasus and Central Asia also face assertive Russian policies. All these nations have suffered the collateral damage of changing ideologies of various administrations in the United States. American disengagement from different parts of the world over the last decade has created a large geopolitical vacuum now filled by Russia, China, and other adversaries.